Deregulatory Upzoning: “Cui Bono?”

A repost from the Livable Portland Blog.

Advocates of progressive planning should take a hard look at the interests behind current pro-growth movements in many cities, their mixed motives and doubtful outcomes. In many cases the motives may have more to do with direct financial benefit than an evidence-based approach to affordability, equity or sustainability.

It is a truism that cities change and grow, and that it is better to take a pro-active stance than a reactive one. We surely need to provide new housing for growing cities, even as we promote equity, justice, and sustainable urban development.

On the other hand, cities are immensely complex systems, and we should be wary of “silver bullet” solutions. As Jane Jacobs and others warned, few such approaches are suited to “the kind of problem a city is” – one that is dynamic, interactive among many variables, and prone to unintended consequences.

One of these silver-bullet approaches is what I will call “build baby build” – that is, maximizing the number of housing units that can be built, especially in the cores, with little regard for what may be in the way. The resulting increase in housing will, it is claimed, ease shortages, lower prices, promote equity, and reduce pressure for unsustainable suburban expansion. If a casualty is a significant loss of heritage structures, that is a necessary price of progress. If a casualty is the democratic participation of citizens who are acting too much like NIMBYs, that is their fault and their problem. If a casualty is the rash dismissal of decades of careful planning – for example, of Oregon’s vaunted land use planning system – well, a new day beckons, with new challenges.

Of course, all of this assumes that such a simplistic silver-bullet approach will be effective – a question we should examine very carefully on the evidence. This is particularly true given the dangers of failure and unintended consequences – as I will discuss below.

In order to put this approach into practice, it is typically necessary to radically deregulate existing planning and zoning regulations – by legislative force if necessary. Such deregulatory upzoning might include (and has included in a number of current Portland, OR. proposals) raising height restrictions, expanding allowable volumes, easing parking requirements, and stripping local boards and neighborhoods of power to assess compatibility with existing neighborhood livability and historic character.

This, then, is a radical agenda of “deregulatory upzoning,” risking an unprecedented transformation of the character of our cities, and discarding years or decades of hard-won gains in urban quality and livability, often derived from careful evaluation and refinement over time. We should at the least carefully assess the evidence before moving forward on such a momentous change. In particular we should ask, as they say in law, cui bono?

The term “cui bono” (to whom is the benefit) is used in law to distinguish the parties that benefit from an action or condition, often to establish the responsibility of hidden actors. Of course the answer by most proponents of the “build baby build” approach is that everyone benefits who seeks more affordable housing, especially those who have been dispossessed, displaced, or otherwise subject to environmental injustice. Everyone benefits from the resulting conservation of farmland, and more sustainable forms of urban development.

As I will discuss in more detail below, this idea is lacking in evidence, contradicted by counter-evidence, and theoretically flawed. In fact the most evident benefit is to some promoters with financial interests, who may or may not be genuinely concerned with housing costs or urban equity. It follows that advocates of progressive planning who may be tempted to align with this agenda should go into any such association with open eyes – perhaps more open than at present.

An example of such well-meaning intentions (at least by some) can be seen in the growing movement, or network of movements, variously known as “Yes In My Back Yard” or “YIMBY,” “Up For Growth,” and other similar groups. These activists have pushed to build many more units, especially in the cores of cities like Portland. These and related efforts have resulted in a growing number of adversarial battles, often pitting long-time allies against one another: affordable housing activists against historic preservationists, environmentalists and farmland preservation advocates against long-time neighborhood livability advocates, and others. In some cases the attacks have become quite personal, heated and disparaging. It is fair to say that, at the least, the climate of constructive civic discourse has not been enhanced in these cities.

Let’s consider the evidence on the claims, and the possible motivations for making them. First, is this deregulatory upzoning actually an effective strategy in creating greater affordability, equity or sustainability? And second, if not, are there other explanations for its aggressive promotion today, aside from the naive ideas of well-meaning activists? Specifically, are there financial beneficiaries from the process, whose interests may be less obvious? Again, cui bono?

First, on the evidence, the most charitable thing that can be said of the current deregulatory upzoning campaign is that it exhibits simplistic (if plausible-sounding) thinking.

Let us start with the fundamental problem for any upzoning strategy for affordability, and that is the dynamic and non-linear nature of real estate markets. Adding desirable units in desirable locations (like the core) can actually make a neighborhood or city more desirable on the whole, and therefore more expensive, not less. Second, the fluidity of demand means that lowering prices can result in “induced demand” from adjacent markets, pushing prices back to their former levels, or (if the result is a surging popularity trend) even higher.

Put differently, it is not a simple linear formula of number of units to cost of units. It matters a great deal what we build, and where we build.

An instructive example can be seen in Vancouver, B.C., where both dynamics have been at work in recent years. That city has tried to build its way out of high prices, while also remaining attractive to outside buyers. The result has been an explosion of new real estate developments, including many new tall building projects. But far from lowering costs, the surge of new units has come even as the city has become, by several measures, the most expensive housing market in North America.

Even so, planners in other cities often seek to emulate the “Vancouver model,” especially the attractive urban scene that has been created along the city’s expansive waterfronts. They seem to overlook the fact that Vancouver is blessed with an extraordinary (and unique) location offering miles of waterfront, scenic mountain geography, and historic assets including the markets at Granville Island (itself the narrow heritage survivor of a plan to demolish it to make way for unremarkable condos in the 1970s). The “attractive urban scene” is also populated almost entirely by relatively wealthy urban elites, much like the planners themselves, and not by a diverse, rank-and-file citizenry.

The “tower envy” shared by so many fans of the Vancouver model also fails to account for inherent problems with tall buildings, as much research has shown. When it comes to affordability, tall buildings are unfortunately an inherently more expensive form of construction, due in part to requirements for costly structural stiffening, and in part to the additional space necessary for egress and service cores. Then too there is the rising cost of land, which tends to be priced for highest and best use. Those factors, combined with the views on offer, mean that most tall residential buildings are sold as expensive condominiums for the wealthy. (Occasionally they include a component of affordable housing, but where it occurs at all this is generally a small percentage, on the order of 10%, with a concomitant rise in the cost of the remaining housing to meet pro forma parameters.)

The other impacts from tall buildings are, of course, on their surroundings, including shading, obstruction of views, and wind effects. Taller buildings also magnify the negative impacts of what citizens may regard as unattractive or even ugly, visually degrading designs. In a five-story building, such a design is a problem for the neighbors, but in a fifty-story building, it is a problem for the entire city.

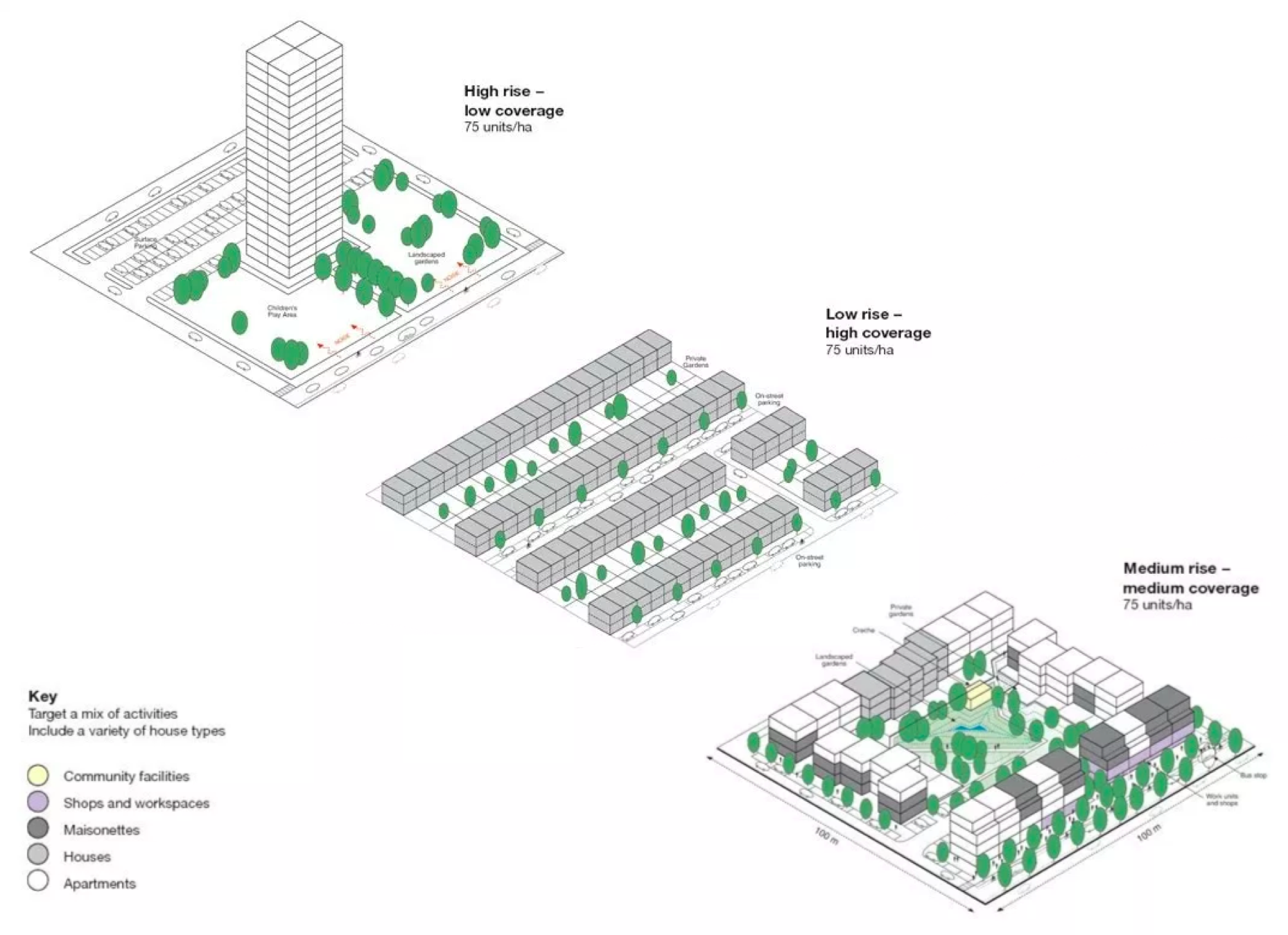

Tall buildings are often justified as a necessary means to achieve higher urban densities, which in turn are considered essential to containing urban sprawl, conserving farmland and natural areas, and providing a more compact and efficient urban form. There are two flaws with this argument. The first is that it is possible to achieve much higher densities than those of most US cities without any tall buildings (a phenomenon that can be readily observed in many other cities, e.g. Paris, Copenhagen et al). This was in fact the finding of a UK House of Commons report on tall buildings: “The proposition that tall buildings are necessary to prevent suburban sprawl is impossible to sustain. They do not necessarily achieve higher densities than mid or low-rise development and in some cases are a less-efficient use of space than alternatives.”

There are several reasons why tall buildings often don’t achieve the densities expected. One, they are typically set back from one another to allow for views, light and privacy. Two, their floor areas are typically constrained by egress (exiting) requirements, including maximum horizontal distance to stairwells. Three, their chief asset is the views they afford, which are more limited in the “deep plan” layouts that would achieve higher density. And four, tall buildings are often set within landscaped areas – Le Corbusier’s “towers in the park” – which further reduces their effective density. In fact, a careful number-crunching exercise reveals the flaws in human psychology, and the tendency to simplistically associate height with density.

The second flaw with the density argument has to do with the supposed value of density itself, which is not scale-free. While moderately high densities are beneficial for resource efficiency and lower emissions, extremely high densities are not proportionately beneficial: many urban benefits, like transportation efficiency, begin to taper off above about 30 units per acre. This is because a person in a four-story building doesn’t travel that much more than a person in a forty-story building – whereas, say, a person in a one-story building on a large lot likely travels a great deal more. Indeed higher densities can carry their own negative impacts, e.g. “canyon effects” concentrating pollutants, “heat island effect” magnifying urban heating, more limited access to sun, light, and so on.

Not all of the proposals are for tall buildings, of course, and many proposals are for mid-rise and low-rise infill projects. Here the objections often center around compatibility with neighborhood character, particularly in historic inner-city neighborhoods. In some cases the new developments are actually replacing demolished historic structures, which often have weak protections. (This is especially true in Oregon, for example.) This is not only bad for heritage, it is bad for the embodied energy and materials that are first destroyed and then duplicated – and often in trendy new structures that may go out of fashion and be demolished sooner. This is not a sustainable approach!

We must also ask whether the idea that central city infill should be prioritized as a key strategy to control loss of farmland and wilderness, as some have argued. Purely from a numbers analysis, the proposition is dubious. For example, the Portland metropolitan area’s “Urban Growth Boundary” (a good proxy for its buildable area) is about 250,000 acres, while the city itself is 85,000 acres, or only 35% of the total. Similarly, the City of Portland’s population is 648,000 while the Portland metropolitan region (including Vancouver) is 2.39 million – almost four times bigger. The area of the Portland core is even smaller – again, on the order of perhaps ten percent.

With those numbers, it must be concluded that there are many more opportunities for many more units outside the core – typically at a lower cost, often without demolishing existing heritage, and often on existing unbuilt or under-utilized land.

What about the idea that the central core offers better infrastructure, better life opportunities, and a better model of sustainability? That amounts to a “monocentric” model of cities, which fails to address the reality – that most city regions are polycentric, with many more residents in suburban cities and urban sub-centers. In the Portland region, those sub-centers include major cities like Gresham and Hillsboro – in their own right the third- and fourth-largest cities in Oregon – as well as urban centers like Portland’s Gateway and Lents. Many people already live and work in these places; so should they not also have good-quality amenities, transportation and mixed use?

There is a one-size-fits-all fallacy in some sustainability circles, that only the centers are truly sustainable, and sub-centers can never be so. This is largely based on the idea that necessary travel to the center requires more energy and emissions. But it neglects the fact that most travel trips are not to the center, and many trips can be captured locally in “complete communities”. In addition, there are many other factors in urban sustainability besides transportation resources. While there are undoubtedly some increased benefits from living in dense cores, again,those benefits taper off as density goes up – and other factors can be equally important. It is naive to assume that everyone will want to live in dense cores – and certainly a disturbing idea that we should force them.

Of course it is more difficult to improve the more distant sub-centers, and make them more desirable. Their markets are not as hot, and investors are not as keen to finance projects. Then too, there are many barriers to good-quality development there. Regulatory burdens are part of the challenge – but not so much because larger and taller buildings are not allowed, for the market will not support such structures anyway. Rather, the barriers are of a more ordinary kind: bureaucracies adding red tape, not coordinating with one another, requiring expensive methods and components, and causing added delay and risk, on top of other factors. These are the bigger barriers to affordable development in any locale.

But the cores offer a seductive target – and an unhelpful one, in relation to goals of affordability, equity and sustainability. The market is eager to build there, but not eager to build affordable or diverse housing. It is all too easy to see projects built that end up moreexpensive than existing stock, and to pat ourselves on the back for adding supply – when in fact we have not addressed the real needs. We have, however, financially rewarded the developers to whom we have given such a remarkable opportunity.

What about the idea that historic structures are inherently more expensive than new ones, and therefore we should not be concerned about their demolition? In fact, older and historic buildings are on average significantly more affordable than the structures that replace them. This can be seen in numerous examples in Portland of tear-downs of houses in the $300,000 price range, replaced by new homes or duplexes in the $600,000 to $1.2 million range, as documented by Restore Oregon. It can also be seen in a simple comparison of rents of older buildings compared to new ones.

In this sense, a reckless supply-side strategy in the cores makes little sense. Indeed, it seems to be a formula for over-heating the cores, and making affordability worse, not better. The gains over more moderate “gentle densification” strategies, as our friend Patrick Condon of the University of British Columbia calls them – working with stakeholders, responding to context, protecting heritage – are unimpressive, and the negative impacts (loss of heritage, loss of livability, political divisiveness) are prohibitively high. And again, most important, there is little evidence, apart from simplistic economic ideology, that “build, baby build” will actually succeed in lowering (or even moderating) prices.

So what strategy would be effective, then?

No one can deny that the problems with affordability and displacement in these cities are real. The question centers on whether there are other more effective strategies — and the answer seems to be yes, in abundance. For example, I have already alluded to the larger pool of opportunities in the 90 percent of regions outside the cores; these include declining malls, under-utilized parking lots, excess rights of way, abandoned or disused buildings, and many other candidate sites. These greyfield locations also offer the opportunity to provide attractive new amenities for outer suburban residents, who are no less deserving of walkable destinations, better support of transportation choices, new public spaces, and additional shops and services – all the ingredients of livable neighborhoods. These sites often also have the important advantage of lower final cost, not only because the land is less expensive, but the staging and construction process is generally simpler. The bureaucratic barriers are often lower as well.

This approach to urbanization is not focused at the center, the “top of the pyramid” regionally speaking – trying in vain to make it cheaper, but in the process likely making the entire region more expensive. Instead, it is focused on the broader urban region, and on a “polycentric” approach, creating many livable centers where residents can live, work and play.

To unlock this much larger pool of potential infill sites, jurisdictions are going to have to be more strategic about the barriers and incentives to development. Yes, regulatory simplification is almost always needed – less a question of raising height or volume restrictions, more a question of streamlining the development process, and incentivizing good development where it is needed, while making bad development pay for the costs it generates (like unneeded demolitions, for example, and excess infrastructure in the case of sprawl).

In addition, different kinds of tax policy tools and other strategic approaches can help to keep existing residents in place while minimizing increases to their rents. Other tax policies can help to moderate speculative investment pressure on prices. For example, Vancouver, B.C.’s provincial government recently raised taxes on foreign investments in real estate, seeking to dampen the speculative surge in foreign-owned real estate.

Finally, my own public involvement work over the years for private developers, governments and NGOs has convinced me that local stakeholders are not the enemy — they are our fellow citizens, after all, with democratic rights — and in fact they can become valuable contributors to a more successful development. What matters is a trust-building commitment to a “win-win” outcome, respecting stakeholder concerns and finding optimal outcomes that address them. One must avoid the easy temptation of stiff-arming, tokenism and other forms of marginalization and disrespect. The anger and opposition that ensues is entirely predictable. Blaming these victims for caring about their homes and neighborhoods seems not only churlish, but disturbingly undemocratic. For in a democracy, these citizens are supposed to have a say about their own public realm, their city, and their heritage – even a duty, to help to protect and improve it.

More recently, having been drafted into my own neighborhood association – an educational experience for a development consultant like me – I have seen that my neighbors do support some kinds of new developments, and might well become (and sometimes do become) advocates for them, even as they oppose others. Why not work with them to identify “pre-entitled” forms of development, with expedited review and permitting? (And therefore lower risk, lower time, and lower cost?) We might not think of this kind of approach as YIMBY – the unquestioning acceptance of any development, and build baby build – but we might call it, say, QUIMBY – “Quality In My Back Yard,” the eagerness to work to get better quality development, more amenities, more protection and enhancement of the existing best qualities of a neighborhood. I have seen this approach work, and I know it is possible. And I submit that it is a better, wiser long-term approach to urban improvement.

Cui Bono?

I began this essay with the question cui bono – to whose benefit is the current wave of reckless regulatory upzoning? One group should be obvious: developers, architects and planners, who stand to earn substantial development income, consulting fees, or secure employment with city departments. (Again I confess here that I am a long-standing member of this community, if a dissident one on this issue.) The motivations of other advocates are not as obvious, but on closer inspection, a connection can often be detected. Although proponents may convince themselves that their own motivations are uncontaminated by self-interest, the facts are often more complicated.

For example, 1000 Friends of Oregon, an anti-sprawl watchdog group – and a group I have supported in the past – has recently become a vociferous booster of deregulatory upzoning and “build baby build” in Portland. At the same time, one of its notable donors is developer Clyde Holland, himself the Chairman of Up For Growth, a national advocacy group for deregulatory upzoning. Mr. Holland was also the largest single donor, in his home state of Washington, to Donald Trump’s 2016 campaign – giving $94,600 – and also the host of a private fundraiser for the president. For many years Donald Trump himself has been known as a proponent of deregulatory upzoning, and an aggressive opponent of local stakeholders (or “NIMBYs”) who question his own developments and their impacts. For advocates of progressive planning, the bullying in today’s environment might have a disturbing echo.

Of course, there is nothing wrong per se with a private entity seeking to make a profit from a real estate development. (Or indeed, supporting whom they please for president.) Of course, private development has produced most of the housing in most parts of the world for a very long time. There is something very wrong, however, with a city or state bending to the siren songs of private interests, adopting a defective growth strategy, sidelining its own well-considered planning systems, and thereby damaging its heritage, its livability, and its democratic processes. Such a reckless, unbalanced approach does not bode well for a better urban future.

The author is a senior researcher in sustainable urban development at KTH Royal Institute of Technology in Stockholm, and also manages the small Portland-based urban think tank Sustasis Foundation. He has worked in sustainable building, development and consulting for governments, businesses, homeowners and nonprofits since 1983, and received his PhD. in architecture at Delft University of Technology after studying at UC Berkeley and The Evergreen State College.

Check Us Out On Facebook!

Check Us Out On Facebook!